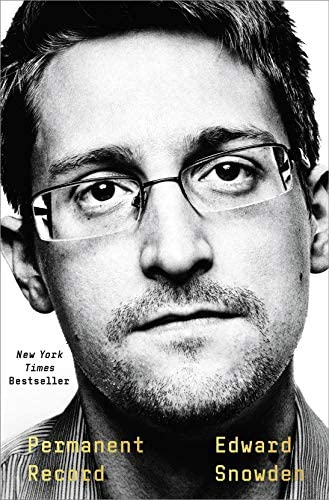

Permanent Record

I.

Permanent record tells the story of Snowden starting from his childhood and up to his exile to Russia. Throughout the course of his life you see how and why he evolves from a patriot excited to serve America, to one disillusioned by the way the U.S. treats its people.

II.

Snowden was a pretty normal kid growing up.. A class clown of sorts, and into technology from a young age. He talks about how it was very different growing up in the 1990s:

In the 1990s, the Internet had yet to fall victim to the greatest inquity in digital history: the move by both government and businesses to link, as intimately as possible, users’ online personas to their offline legal identity. Kids used to be able to go online and say the dumbest things one day without having to be held accountable for them the next.

Today, this is no longer the case of course. The things you say online in your childhood can very easily come back to haunt you.

Snowden stands strongly pro-privacy, and this is made clear throughout the book. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much nuanced discussion in the book about why privacy is good or bad. It takes “privacy is bad” as an obvious assumption. An obvious counter example showing that privacy is more than one dimensional is murder. People shouldn’t be able to commit murder and keep that private right?

Even so, privacy is a topic this book got me to think more deeply about and I’ll be writing more about it in the future.

III.

Quips throughout the book like to poke at how problematic government organization hiring practices are. There are many comments about government employees who don’t appear to have worked in years, and about various loopholes which are used to overhire and go over budget.

Here he talks about agencies getting around the legislative limit on hiring, and easily acquiring funds from Congress via appeals to emotion:

Every agency has a head count, a legislative limit that dictates the number of people it can hire to do a certain type of work. But contractors, because they’re not directly employed by the federal government, aren’t included in that number. The agencies can hire as many of them as they can pay for, and they can pay for as many of them as they want—all they have to do is testify to a few select congressional subcommittees that the terrorists are coming for our children, or the Russians are in our emails, or the Chinese are in our power grid. Congress never says no to this type of begging, which is actually a kind of threat, and reliably capitulates to the IC’s demands.

In addition to this loophole causing overspending, it has the downside of giving outsider private contractors access to highly sensitive data:

It was particularly bizarre to me that most of the systems engineering and systems administration jobs that were out there were private, because these positions came with almost universal access to the employer’s digital existence. It’s unimaginable that a major bank or even a social media outfit would hire outsiders for systems-level work. In the context of the US government, however, restructuring your intelligence agencies so that your most sensitive systems were being run by somebody who didn’t really work for you was what passed for innovation.

What should be done about this? It’s not clear. The libertarian response would be to let the market take care of things.

As far as work ethic and incentives go, it was fun to here the stories Snowden would share about one of his former coworkers, Frank:

He enjoyed telling me, and everyone else, that he didn’t really know anything about computing and didn’t understand why they’d put him on such an important team. He used to say that “contracting was the third biggest scam in Washington,” after the income tax and Congress. He claimed he’d advised his boss that he’d be “next to useless” when they suggested moving him to the server team, but they moved him just the same. By his own account, all he’d done at work for the better part of the last decade was sit around and read books, though sometimes he’d also play games of solitaire—with a real deck of cards, not on the computer, of course—and reminisce about former wives (“she was a keeper”) and girlfriends (“she took my car but it was worth it”). Sometimes he’d just pace all night and reload the Drudge Report.

It’s quite something when somebody tells their boss they will be “next to useless” in a position, and the boss follows through anyways!

IV.

Government power is a topic near and dear to Snowden’s heart. He likes to emphasize that the government has way more power than anybody seems to realize. It’s one of those things that everybody will appear to acknowledge if you directly ask them about it, but then completely forgets about in all other scenarios. Like some sort of Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect.

One example is the Internet. Some people like to imagine it as decentralized, but when you take a closer look you realize how centralized it really is:

The cables and satellites, the servers and towers—so much of the infrastructure of the Internet is under US control that over 90 percent of the world’s Internet traffic passes through technologies developed, owned, and/or operated by the American government and American businesses, most of which are physically located on American territory.

The Bitcoin maxis love to talk about how Bitcoin is censorship resistant money, but how does one defend against the attack vector of America filtering Bitcoin packets which pass through its internet space? In fact, China is already doing exactly that with the great firewall of China!

It may be possible for Bitcoin to exist in some form while under attack from the U.S. government, but it’s hard to imagine it thriving in such a scenarios. The question then becomes whether or not the U.S. will attack Bitcoin. I guess in the worst case you can always turn to IP over Avian Carriers.

As far as whether or not you can expect the U.S. to be agentic in using its power, Snowden has some thoughts:

According to the report, it was the government’s position that the NSA could collect whatever communications records it wanted to, without having to get a warrant, because it could only be said to have acquired or obtained them, in the legal sense, if and when the agency “searched for and retrieved” them from its database.

Here we see that the U.S. is willing to stretch the meanings of english words in order to increase its power. It was a bit inconvenient that a warrant was technically required in order to “acquire or obtain” communication records, so the someone had the ingenious idea of redefining “acquire or obtain” to refer to the action of reading it from the database… This highlights that an important component to preventing government overreach is transparency. That being said, this type of two way accountability is extremely difficult to implement without compromising actually secret information. For more on this topic you can check out The Transparent Society.

At one point Snowden turns his attention to the U.S. census and the pretenses which surround it. The Constitution establishes the “official” purpose of the American census as determining the official federal count of each state’s population in order to determine its proportional delegation to the House of Representatives. But that was somewhat of a revisionist principle. In authoritarian governments, including the British monarchy that ruled the colonies, the census had traditionally been used as a method of assessing taxes and ascertaining the number of young men eligible for military conscription. The real motivation for the census is to increase the legibility of the population so that it can be better controlled.

Once you see it that way, digital technology becomes a lot scarier:

Digital technology didn’t just further streamline such accounting—it is rendering it obsolete. Mass surveillance is now a never-ending census, substantially more dangerous than any questionnaire sent through the mail. All our devices, from our phones to our computers, are basically miniature census-takers we carry in our backpacks and in our pockets—census-takers that remember everything and forgive nothing.

Technology has been getting stronger and stronger. Just over the course of Snowden’s career, the CIA’s goal went from being able to store intelligence for days, to weeks, to months, to five years or more after its collection. The NSA’s conventional wisdom was that there was no point in collecting anything unless they could store it until it was useful, and there was no way to predict when exactly that would be. This rationalization was fuel for the agency’s ultimate dream, which is permanency—to store all of the files it has ever collected or produced for perpetuity, and so create a perfect memory. The permanent record.

There you have it. The permanent record… We can only hope that it be used for good and not for evil. Which raises the question, who controls the permanent record?

Here is one thing that the disorganized CIA didn’t quite understand at the time, and that no major American employer outside of Silicon Valley understood, either: the computer guy knows everything, or rather can know everything. The higher up this employee is, and the more systems-level privileges he has, the more access he has to virtually every byte of his employer’s digital existence.

I think this is still something that most people still don’t realize, and that’s pretty amazing. It’s pretty amazing that this idea has been able to remain an anti-meme and stay out of the zeitgeist. People use technology to store all of their deepest secrets and private conversations, and very rarely does it ever cross anyone’s mind that other people can access this information without your permission. Google can see your emails, Facebook can see your messenger messages, and these companies are under the jursidiction of the US government which can ask for any of this data.

V.

Eventually the book gets to the story of how Snowden was actually able to obtain the documents he needed to alert the public and fly with them to Hong Kong. He had to pull off some James Bond type stunts and constantly plan 10 steps ahead. It’s a miracle that he was actually able to make it happen, at one point smuggling a micro SD card inside of a Rubik’s Cube.

Each time I left, I was petrified. I’d have to force myself not to think about the SD card. When you think about it, you act differently, suspiciously.

There’s an interesting dynamic between him and his girlfriend throughout the process. Despite executing on the whisteblowing being his main focus for months, and odd behaviors it requires of him, he maintains the self-control to not tell a single word about anything to his girlfriend, Lindsay.

After getting the documents out of his office, he needs to get them to Hong Kong. One morning Lindsay leaves the house for a camping trip, and he takes his opportunity, buying a one way flight to Hong Kong in cash. When Lindsay returns home she finds an empty house and has no idea what to make of it, at one point questioning if he is having an affair in her diary:

I’m thinking, What if he’s off having an affair? Who is she?

Once the FBI figures out what Snowden has done, they download all of Lindsay’s emails and conversations with Snowden and interrogate her. They are amazed that she has no information to share with them.

When the articles go live with the document’s Snowden obtained, the US becomes split on what to make of Snowden. Supporters claim he is a hero, while detractors say he is un-American. Here Snowden shares some of his perspective on the way American’s see the act of disclosure:

Today, “leaking” and “whistleblowing” are often treated as interchangeable. But to my mind, the term “leaking” should be used differently than it commonly is. It should be used to describe acts of disclosure done not out of public interest but out of self-interest, or in pursuit of institutional or political aims. To be more precise, I understand a leak as something closer to a “plant,” or an incidence of “propaganda-seeding”: the selective release of protected information in order to sway popular opinion or affect the course of decision making. It is rare for even a day to go by in which some “unnamed” or “anonymous” senior government official does not leak, by way of a hint or tip to a journalist, some classified item that advances their own agenda or the efforts of their agency or party.

And as far as the law goes, Snowden makes it clear that he isn’t happy with the current situation:

American law makes no distinction between providing classified information to the press in the public interest and providing it, even selling it, to the enemy. The only opinion I’ve ever found to contradict this came from my first indoctrination into the IC: there, I was told that it was in fact slightly better to offer secrets for sale to the enemy than to offer them for free to a domestic reporter. A reporter will tell the public, whereas an enemy is unlikely to share its prize even with its allies.

Giving secrets to reporters is even worse than giving them to enemies!

VI.

A topic related to privacy is law enforcement. Snowden is afraid of how technological society is becoming, and its implication for government power and enforcement. Where are we headed?

I wondered whether this would be the final but grotesque fulfillment of the original American promise that all citizens would be equal before the law: an equality of oppression through total automated law enforcement. I imagined the future SmartFridge stationed in my kitchen, monitoring my conduct and habits, and using my tendency to drink straight from the carton or not wash my hands to evaluate the probability of my being a felon.

Snowden points out that a world in which every law is always enforced would be a world in which everyone was a criminal:

Most of our lives, even if we don’t realize it, occur not in black and white but in a gray area, where we jaywalk, put trash in the recycling bin and recyclables in the trash, ride our bicycles in the improper lane, and borrow a stranger’s Wi-Fi to download a book that we didn’t pay for. Put simply, a world in which every law is always enforced would be a world in which everyone was a criminal.

Similar to his discussions on privacy, there isn’t much nuance here, but the ideas did push me to think harder about these ideas. The helpful question for digging deeper is: what is the point of law enforcement?

Law enforcement isn’t an end in itself, but a means to some other end. What is that end, and how do we optimize law enforcement with respect to it? That’s a controversial question to be investigated another day.